Luxury “Made in China”: the great scandal of the industry

A bag with the label “Made in Italy” displayed in an exclusive boutique may have been born thousands of miles away from Europe. Today we know that some of the most prestigious luxury brands in the world manufacture much of their products in China or other Asian countries, only to label them as European and sell them at exorbitant prices. This investigative report explores recent cases that have uncovered this practice, the techniques the industry uses to conceal it, the legal framework that allows it, the reactions it has provoked, and the ethical implications that challenge the true meaning of luxury.

Exposed luxury brands: recent cases

In recent days, social media –especially TikTok– has been filled with surprising revelations about the true origin of luxury products. Users identified as Chinese manufacturers have showcased factories and production processes, claiming that many “premium” items with a European label are actually produced in China. In a viral video, a Chinese entrepreneur even asserts that “around 80% of luxury bags are made in China, even if the label says otherwise”. According to this manufacturer, for more than 30 years, their OEM factory has produced for major brands like Gucci, Prada, or Louis Vuitton, crafting bags “with precision” while Western houses take the lion’s share of the profits. “90% of the price paid is for the logo,” states another producer while comparing an exclusive Hermès Birkin bag priced at $20,000 with its actual manufacturing cost of just $1,400.

These “digital whistleblowers” have provided concrete examples. A young person showed that the Chinese factory Sitoy Handbag would supply Prada, Coach, and other brands (affordable “luxury”), where a handbag that costs more than $500 in stores can be purchased for $50-$100 at the source. Another video detailed how Lululemon athletic leggings (a high-priced brand, although not traditional luxury) sold for $100 are produced in the same Chinese factories that manufacture garments for mass brands, with a unit cost of just $5. The reaction was immediate: “And you paying 1,500 for that handbag?”, a media outlet headlined while summarizing the outrage of consumers who feel cheated. Many shoppers expressed shock upon discovering that the handbag proudly displayed as a status symbol (Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Gucci…) may have “cost less than 100 dollars to produce”, despite selling for thousands.

It is not just rumors on social media. Journalistic and judicial investigations in Europe have confirmed that this practice exists. In 2024, the Milan Public Prosecutor uncovered a network of illegal subcontractors linked to Dior and Armani that produced luxury handbags under exploitative conditions. A Chinese-owned supplier manufactured Dior handbag models for just 53 euros per piece, which Dior then sold in stores for 2,600 euros. Similarly, subcontractors paid seamstresses 2 or 3 euros per hour for shifts of 10-15 hours. They produced bags that were sold to Armani’s intermediary for 93 euros. These bags ended up in boutiques at 1,800 euros. The workshops involved – located not in Asia, but in the outskirts of Milan – kept workers (mostly Chinese migrants) living and sleeping in the facilities to sew day and night, even on holidays, to meet the demand. Italian authorities described this situation as “a widespread and consolidated manufacturing method” in the luxury sector to cut costs at all costs. In other words, even within Europe, the hidden production scheme was replicated: cheap labor, precarious conditions, and a chasm between the real cost and the selling price.

The Hidden Manufacturing: Outsourcing and Undercover Techniques

If a product is made in Asia, how does it legally manage to wear the label “Made in Europe”? The answer lies in the complex subcontracting chains that luxury brands have perfected to conceal the true origin of their items. Broadly speaking, this is how the industrial magic trick works:

- Mass offshore production: Most of the process (material cutting, sewing, and assembly) takes place in low-cost Asian factories, primarily in China. These plants at the same time work for multiple global brands, leveraging economies of scale and cheap labor. Major OEM manufacturers in China quietly run as ghost suppliers for European brands, without their names being known to the public.

- Final finishing and assembly in Europe: Products leave Asia nearly finished and are shipped to workshops in Italy, France, or other European countries for final touches. This can involve adding metal fittings, sewing part of the lining, placing the label, or simply packaging the piece. By conducting this last phase on European soil, the brand can now legally stamp “Made in Italy” or “Made in France” on the item, even though 90% of its manufacturing was done abroad. A former employee crudely summarizes it: in some cases, “the only Italian part is the box or the final stitching” of the product.

- Legal loophole in origin labeling: This practice exploits a gap in international trade regulations. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the European Union, the country of origin of a good is determined by where its “last major transformation” occurred. In practice, this means that even though 80-90% of the labor and components come from China, merely conducting the last significant step of manufacturing in Europe is enough for the product to be labeled as European. The law is not being violated – that labeling is technically allowed – but it is still evading its spirit, to the point that Made in Italy can mean “assembled in Italy from parts made in China”.

- Contractual secrecy and NDAs: Large brands often protect these arrangements with strict confidentiality agreements with their suppliers. Asian factories run in the shadows, contractually obligated not to reveal for whom they produce. For this reason, we rarely see a Louis Vuitton or Gucci publicly admit what percentage of their collections comes from Asia. This deliberate opacity keeps the facade of “European craftsmanship” intact in the eyes of the buyer.

In summary, the industry has woven a global network where design and marketing are in Paris or Milan, but the stitching is in Guangzhou or Shenzhen, although the customer never notices on the label. “Designed in France, made in China and finished in Italy” very well be the true technical specification of many contemporary luxury goods.

Labels Under Scrutiny: The Legal Framework and How They Are Circumvented

The case presented raises an uncomfortable question: Is it legal to sell something manufactured mostly in Asia as “Made in Europe”? The answer, to some extent, is yes. As we have seen, international (WTO) and European trade regulations allow the origin of a product to be defined by its last significant transformation. Thus, a bag sewn in China but whose handle is attached in Italy can legitimately carry the “Made in Italy” label. This rule was created to make global trade easier, but brands have turned it into a legal loophole to mask their supply chains.

In the European Union, labeling the country of origin on non-food products is not always mandatory, but if a company chooses to show it (and in luxury goods, it is key for the image), it must adhere to the definition of origin mentioned. It is not fraud in the strict sense, because it complies with the letter of the law: indeed, something in the process occurred in the country listed on the label. Nonetheless, many classify this practice as deceptive to consumers, as it leads one to believe that the entire artisanal process took place there. Consumer organizations argue that “Made in Italy” has become an ambiguous term, used more as a marketing tool than as truthful information.

Authorities are beginning to take notice. In Italy – a country protective of the Made in Italy designation – the Judiciary has proposed strengthening controls over local suppliers and workshops after discovering exploitation cases linked to Dior and Armani. The Milan Court suggested a code of best practices so that brands audit their subcontractors with greater rigor and confirm compliance with labor laws. While these guidelines are not yet binding, they represent a wake-up call for the entire industry. “We have noticed that companies do not invest enough in control systems… They simply take advantage of ultra-low prices to maximize profits,” explained Fabio Roia, president of the Milanese Court. In his investigation, Roia found luxury handbags offered at such low prices by clandestine suppliers that “they should have raised alarms” about their origin.

Outside of Italy, there is a question of whether greater mandatory transparency in labeling is needed. For instance, requiring labels to show all the countries involved (“Made in China and finished in Italy”), or at least a percentage of domestic content. Some high-end brands already voluntarily detail “Made in Italy with imported materials” on certain pieces, but these are exceptions. For the moment, the global legal framework provides enough loopholes for business to continue as is. The burden then falls on vigilance and public pressure: the more informed consumers are, the harder it will be to keep misleading labels without consequences.

Consumer, Media, and Expert Reactions

The revelations about luxury “Made in China” have sparked strong and divided reactions. Many consumers express outrage and feelings of deception. “I was sold an illusion of European craftsmanship, and it turned out to be mass-produced in China,” they lament on social media. Personal stories have gone viral: customers who, upon closely inspecting their expensive items, found hidden tags saying Made in PRC (China), or who, after learning about these reports, swear never to buy traditional luxury again unless they are guaranteed the product’s origin. The conversation has particularly resonated among young buyers (millennials and Gen Z), who are more accustomed to scrutinizing the ethics behind brands. Informal surveys show that a large percentage demands transparency and believes that paying so much money is only justified if the product is truly special in its crafting, not if it comes from the same factory that supplies mass brands.

The international press has not let the news go unnoticed either. Media in various countries have published investigations, combining TikTok’s complaints with independent verifications. For instance, The Independent from the UK and France 24 analyzed these viral videos: they consulted industry experts and concluded that some claims are exaggerated, and even warned that certain videos are intended to promote unauthorized imitations taking advantage of the controversy. In other words, not everything that glitters is gold on TikTok: alongside uncomfortable truths, there are opportunists (unofficial factories or counterfeiters) who spread biased information to sell their own products. Nevertheless, even with this caution, it became clear that the practice of outsourcing luxury production is real – judicial investigations and cited reports confirm this – just that the exact proportions vary by brand.

Fashion and luxury specialists have provided context to this debate. Many point out that outsourcing does not necessarily equate to poor quality: prominent Asian manufacturers have the equipment and skills to produce excellent products if the brand demands it. In fact, some luxury executives admit off the record that “China can manufacture luxury just as well or even better than Europe, just without the mystique of the name.” From China, some suppliers proudly defend their work: “Yes, we produce it, and it’s of quality. China doesn’t just produce cheaply; it also produces luxury… just without the European logo,” they proclaimed on social media after the controversy unfolded.

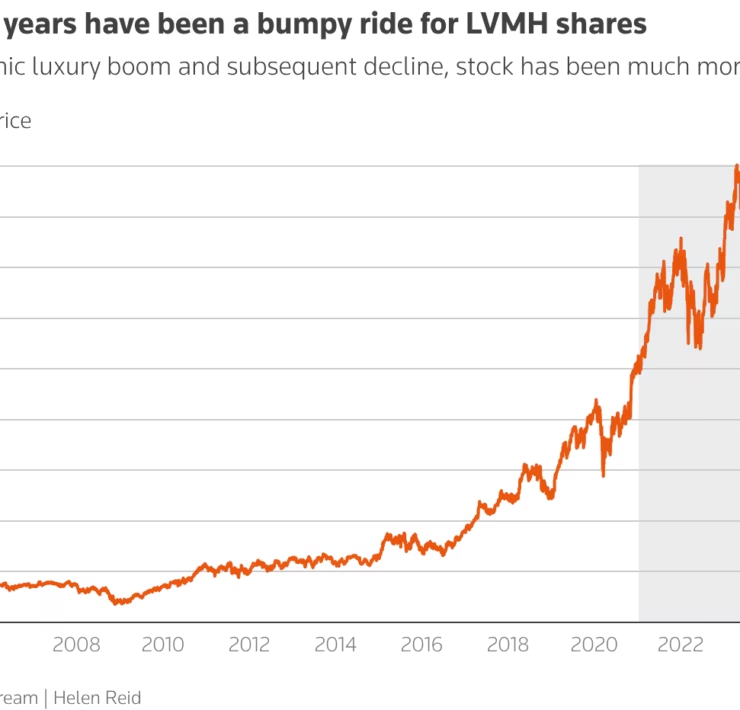

On the other hand, financial analysts point out that fashion houses have been moving production to cheaper countries for protecting their profit margins, especially since the 2008 crisis. But, they do not publicize it for fear of damaging their aura of exclusivity. “It’s the worst-kept secret in the industry,” ironically comments a former executive: everyone does it, but no one says so. This explains why the first reaction of brands to the scandal was one of silence or denial. No major house issued extensive statements on the matter. LVMH (owner of Louis Vuitton, Dior, Fendi, etc.) declined to comment on the specific accusations, while Prada, Gucci, and others have preferred to emphasize the quality of their materials and controls, without addressing where each item is sewn. Armani, after its case in Italy, stated succinctly that “it always seeks to reduce abuses in its supply chain” and that it will cooperate with authorities. In general, brands shield themselves by claiming that they uphold uniform standards regardless of the country of manufacture – arguing that a bag made in China on their behalf can be just as good as one made in Florence – yet they avoid confirming specific figures or locations.

A prominent figure in exposing the reality of costs has been Tanner Leatherstein, an expert in leather who has become popular for dismantling luxury items in his videos. Leatherstein takes bags from prestigious brands, disassembles them piece by piece, and calculates their true production cost. His findings are revealing: “My estimate for the cost of the leather is $100. For accessories and assembly, another $160. In total, it shouldn’t cost more than $260 to make a bag like this”, he says about the classic Louis Vuitton Neverfull, for which he paid over $2,700. He concludes that, indeed, much of the price corresponds to intangibles like brand, distribution, and exclusivity, rather than materials or labor. His phrase “you pay for status, not for the object” resonates among followers who now question whether it is worth investing in these products. Leatherstein also compares that estimated cost of $260 with that of a status-free logo independent brand handbag, estimating that a similar one cost $600-$700 – still less than a third of the LV. This type of analysis has led many to question the profit margins of luxury brands and to ask: what am I really paying for when I buy luxury?

In summary, the reactions range from outrage and feelings of deception among consumers, to media and expert scrutiny that adds nuances (quality, counterfeits, historical context), to a nascent self-criticism in the industry that has preferred to stay silent while assessing the reputational damage. The truth is that the issue has escalated enough for luxury to face a small crisis of confidence.

Ethical Implications: The Concept of Luxury in Question

This whole scandal triggers a deeper reflection: What does “luxury” mean when manufacturing conditions resemble those of fast fashion? Traditionally, a luxury item justified its high price by the excellence of its tailoring, the craftsmanship, the hours of expert work, and the scarcity. Nonetheless, the revealed practices suggest that in many cases, today’s luxury has become a marketing exercise, where the product is essentially the same as a mid-range one, just with a prestigious logo and a well-told story.

The gap between myth and reality is ethically problematic. On one hand, we have well-intentioned consumers paying, let’s say, $5,000 for a handbag, assuming that it comes from centuries-old workshops in France or Italy, with master leatherworkers crafting it by hand. On the other hand, we discover that that handbag came from an industrial factory in Asia, in a mass production line akin to those for common products. As one sharp comment on social media pointed out: “These are not unique treasures made by artisans in Milan; in many cases, they are factory goods produced using the same approaches and materials as mid-range items.” The authenticity of luxury is thus called into question.

Even more serious are the implications for labor rights and social justice. Luxury, with its high margins, can afford – pun intended – to pay decent wages and keep high standards everywhere. Still, cases like Italy show that vulnerable labor has been abused to inflate profits. Exploited seamstress workers, marathon shifts in clandestine workshops without safety measures, miserable wages of 2 euros an hour in the 21st century… These are harsh realities difficult to reconcile with the glamorous image of luxury fashion. That bags worth thousands of euros are stitched by immigrants crammed together who sleep next to their sewing machines is a situation bordering on inhuman and shows a major ethical failure. Italian authorities have reported that this “violation of labor standards” is also unfair competition that harms manufacturers who do follow the laws. In other words, if the entire sector played fair, prices would be somewhat lower or profits more moderate, but at least rights would not be trampled upon. Today, unfortunately, the opulence of some brands seems to be sustained by hidden exploitation.

There is also the issue of honesty with the consumer. Although companies argue that “legal is equal to ethical,” many disagree. The consensus among marketing and business ethics experts is that misleading the public erodes trust in the long run. Selling a fantasy is part of luxury, yes – it sells a dream of status, belonging to an elite, tradition – but when that dream is based on misleading claims about factual facts (like origin and manufacturing techniques), we cross a dangerous line. “The problem here is not legality, it is honesty,” wrote an analyst on this topic. While the truth was not known, people believed they were paying for European craftsmanship, but in reality, they were paying for a mass-produced item with just a European label added at the end. Now that the truth is beginning to surface, some feel that luxury has failed them. The risk for brands is that this carefully constructed halo of exclusivity can crumble, and with it, the customer’s willingness to pay premium prices vanish.

Finally, these revelations touch on the nerve center of sustainability and responsibility. In recent years, the fast fashion industry has faced harsh criticism for relying on precarious labor in developing countries. Luxury was once seen apart from that – at least in popular perception – linked with “the good, clean and fair”. Discovering that luxury can hide production chains akin to those of fast fashion is a reputational blow. Some critics speak of hypocrisy: the same brands that promote values of excellence, tradition, and even philanthropy would be applying a double moral standard internally by not ensuring decent conditions for all their workers throughout the supply chain. This opens up an uncomfortable debate for the sector: Can luxury continue to proclaim values of quality and exclusivity while resorting to ethical shortcuts?

In conclusion, the ethical implications encompass consumer deception, labor exploitation, and the erosion of the authenticity of luxury as a concept. If luxury ceases to be synonymous with the best of the best in all aspects (materials, craftsmanship, human treatment), it risks becoming simply an expensive label devoid of content, which in the long run would undermine its very reason for being.

Transparency as a Trend: Changes in Consumer Behavior

In the face of this wave of information, consumers are changing their habits and expectations about high-end brands. A trend towards conscious consumption in fashion had been developing, but now it is clearly extending to luxury: buyers want to know the truth behind the product. More and more people are asking “what exactly am I paying for: the artisanal quality, the label, or just the prestige?” This growing awareness is leading to demands for answers.

In 2024 and 2025, there has been a rise of consumers who value transparency and ethics. A specialized report anticipated that luxury customers “will demand greater transparency, ethical sourcing, and environmentally responsible manufacturing processes.” This implies that brands can no longer simply hide behind their name; they must be prepared to offer clear information about where, how, and by whom each item is made. In fact, some young firms have made transparency their main appeal: they share videos of their workshops, publish cost breakdowns (raw materials, labor, margin), and even pinpoint the craftsmen who create each piece. This model of openness, unthinkable in traditional luxury houses, is attracting a segment of consumers tired of secrecy.

Moreover, a niche of “different luxury” brands has emerged, promoting different values: local productions in small series, sustainable materials, and more affordable prices, renouncing part of the margin to be more accessible. Although they do not have the historic name of a Vuitton or a Prada, they are gaining ground among buyers who prefer a product with “meaningful history” and ethics, even if it does not flaunt a recognized logo. For example, in the sector of bags and accessories, independent workshops in Spain, France, or Latin America have emerged, openly communicating: “we hire local artisans, pay fair wages, this piece took X hours to make, the materials come from such a place…”. Such initiatives resonate particularly with younger generations, who reward with their loyalty companies that align with their values.

Another derived phenomenon is the growth of the luxury resale market (second hand). Faced with uncertainty about current production, some consumers choose to buy vintage or second-hand pieces from eras when, in theory, they were entirely manufactured in Europe. Resale platforms have reported that buyers ask about the year and place of manufacture of a handbag before purchasing it, seeking “Made in France 1985” instead of a more recent one that has been made offshore. Paradoxically, the old regains value due to its guaranteed authenticity, while the new is inspected for scrutiny.

Established brands are beginning to respond (albeit timidly) to this demand for transparency. Some have added sections on their websites about “our workshops,” showcasing photos of artisans in Europe—though without detailing what percentage of total production they represent. Others have committed to more frequent audits of their supply chains and to publish social responsibility reports. The giant LVMH, for example, indicated in 2023 that it conducted 1,725 audits of suppliers during the year, suggesting that it is monitoring its global network (though it did not specify results).

Yet, a healthy skepticism persists among the public: promises must be translated into verifiable facts. Hence the importance of technological initiatives like blockchain applied to luxury (which we will discuss in the next section), that allow a customer to trace the journey of their item from the workshop to the store. In this context, a slogan is increasingly heard in the sector: “luxury will be transparent, or it will not be”. Transparency is becoming not just a virtue but a necessity for the long-term survival of brands.

It is also worth mentioning that some consumers, after the first outrage, have adopted a pragmatic stance: “if the quality is good, I don’t care too much where it was made, but don’t lie to me with the label.” This group would be willing to continue buying luxury even if it’s made in China, as long as the brand is honest and maintains high standards. Yet, they are a minority for now. The majority seem to lean towards punishing with their wallets those brands perceived as dishonest and supporting those that show integrity.

Ultimately, we are witnessing a shift in mindset: from a passive buyer who only looked for the logo, to an active and informed buyer who asks, compares, and decides based on how the product aligns with their values. Luxury, which has always thrived on a carefully constructed mystique, faces the challenge of fitting into an era of hyper-information and ethical demands. And as the saying goes, “the customer is always right”: if luxury customers want transparency and ethics, brands will have to adapt or risk losing relevance.

Pressure for Change: Towards a More Ethical and Transparent Luxury

Where is the luxury industry headed after these revelations? In the short to medium term, significant changes are anticipated driven by public pressure and regulatory scrutiny. While transformations in such a traditional sector are usually slow, analysts agree that we are moving towards a more transparent, responsible, and local luxury in its practices, under threat of losing consumer trust.

In the corporate realm, major parent companies (LVMH, Kering, Richemont, Prada Group, etc.) are strengthening their compliance and traceability departments. A significant milestone was the creation of the Aura Blockchain Consortium by LVMH, Prada, and Richemont in 2021, a joint platform that uses blockchain to track the value chain of luxury products. Aura’s promise is that customers can access, via a digital certificate, the entire history of an item: from the origin of its materials, through the manufacturing stages, to the store where it was sold. Officially, it was presented as a tool against counterfeiting and to guarantee authenticity, but implicitly it also means that every step of production is recorded. If brands wanted to (that is the key: want), they give buyers access to that detailed information. The mere fact that they invest in this platform reflects that “traceability has become an obsession for major luxury firms”. In other words, they acknowledge that transparency is no longer optional.

In parallel, we see changes in regulation. Although at the European Union level there is no immediate prospect of a law requiring “Made in X and Y” labeling, the pressure from certain countries like Italy will lead to stricter national regulations. For example, Italy will legislate to protect its designation of origin, requiring a least percentage of local manufacturing to use Made in Italy. Additionally, in key markets like the United States, authorities (FTC) have historically been strict about misleading Made in USA claims; it is possible that they will extend this scrutiny to imports, ensuring that items labeled as European genuinely come from Europe.

Another consequence is a rethinking of supply chains by brands. Some choose to move part of their production to Europe (or to countries with higher labor costs but artisanal prestige) to regain credibility. In fact, movements are already being observed: brands announcing the opening of new workshops in Italy, France, or Spain, creating local jobs. While the motivation is political (to look good with governments) or practical (to avoid tariffs and logistical risks), it also supports the narrative of authenticity. It would not be surprising if, in the coming years, companies that earlier outsourced everything start proudly displaying that “80% of our products are made in Europe” (changing the narrative from the current 80% made in China).

On the consumer side, the aforementioned trend towards ethical consumption will undoubtedly strengthen. The new generations have grown up with social and environmental awareness, extending these criteria to all their purchases. Luxury will be no exception. If a luxury brand fails to pass a customer’s moral filter (due to opaque or questionable practices), the customer will have alternatives: from other traditional brands that have improved their policies, to new, more ethical players, or simply spending their money on products from other industries (experiences, technology) instead of fashion. In the worst-case scenario for the sector, there is an erosion of aspirationality: luxury will cease to be desirable because it is linked with deception or injustice. Avoiding this scenario is a priority for firms, hence they must reclaim the positive narrative of luxury through tangible actions.

Finally, we can see a reevaluation of authentic craftsmanship. The true European artisan workshops, many of which had been displaced by industrial production, will experience a renaissance supported by the demand for genuineness. Smaller brands with 100% local production occupy a larger niche. Even the major houses invest in training new artisans and expanding their own workshops, even if it costs them more, as a way to preserve their legacy and differentiation. After all, luxury was born from craftsmanship; it needs to return to its roots to avoid being lost.

In summary, the luxury industry is at a historical crossroads. Opaque practices and the relentless pursuit of profitability have collided with the values of an era defined by transparent information and conscious consumption. A future is emerging where the luxury that thrives will be one that embraces transparency, ensures ethical conditions throughout its supply chain, and reinforces with actions its promise of exceptional quality. As some industry leaders have stated: the luxury of the future will be responsible and transparent… or it will not exist.

Share/Compártelo

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Threads (Opens in new window) Threads

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- More

Related

Discover more from LUXONOMY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.